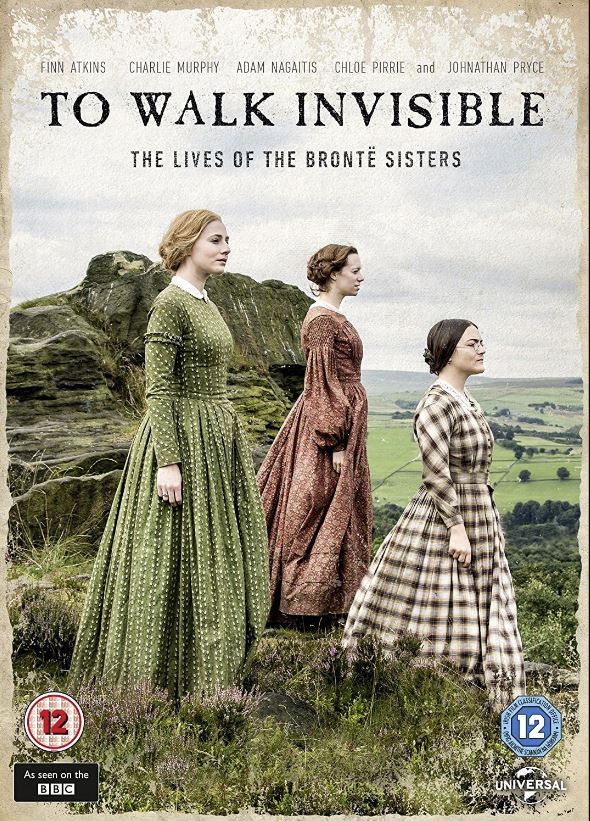

- Today’s Movie: To Walk Invisible

- Year of Release: 2016

- Stars: Finn Atkins, Charlie Murphy, Chloe Pirrie

- Director: Sally Wainwright

This movie is not on my list of essential films.

NOTE: This installment of Sports Analaogies Hidden in Classic Movies is not being done as part of a blog-a-thon. Instead, this is a monthly event hosted by MovieRob called Genre Grandeur. The way it works is every month MovieRob chooses a film blogger to pick a topic and a movie to write about, then also picks a movie for MovieRob to review. At the end of the month, MovieRob posts the reviews of all the participants.

For September of 2024, the honor of being the “guest picker” went to Emily of The Flapper Dame, and the topic is “Movies With/About Sisters.”

The Story:

The plot of this film opens in 1845 and features five members of the Brontë family. It begins with the patriarch Patrick (played by Jonathan Pryce) and his son Branwell (played by Adam Nagaitis), but the sisters Charlotte (played by Finn Atkins), Emily (played by Chloe Pirrie), and Anne (played by Charlie Murphy) quickly become the focal point. The catalyst for what is to come begins with the brother Branwell being dismissed from his job as a tutor. His sister Anne then resigns from her position as a governess with the same family. As a result, it is left to Anne to tell the rest of the family why Branwell was fired; he was having an affair with the matriarch of the house.

The sisters have a problem at this point. Without Branwell and Anne’s income, the family is in dire straits financially. Their father Patrick is blind and in bad health, and Branwell is a liar, a heavy drinker, and can’t keep money in his pocket. Even more troubling is the family home belongs to the parish, meaning when Patrick dies, the sisters will be dependent on Branwell.

This is when the role of writing enters the picture. While Anne tells Charlotte she still writes, Charlotte admits giving it up as it frightens her. But Charlotte is also terrified of being is financially dependent on Branwell. As such, she asks him about his plans for the future.

Branwell tells Charlotte he has published a few poems, but has his sights set on writing a novel because there’s potentially more money involved. This gives Charlotte cause to wonder if she and her sisters could publish their own works. She searches Emily’s room and discovers her poems, but Emily is infuriated at the invasion of her privacy. Despite this, Charlotte believes Emily’s work is brilliant, and Anne now becomes intrigued by the idea of publishing her own work.

Anne shows her writing to Charlotte, who is largely unimpressed. But it does convince Charlotte the sisters should publish a volume of poetry they can use to establish themselves. Together they pay to have Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell published. They use pseudonyms so they cannot be identified as women, and to keep the publication unknown to Patrick and Branwell.

Meanwhile, Branwell has discovered his former lover’s husband has died, but his will stipulated she will lose her money and her house if she remarries or is seen with Branwell. This drives Branwell further into the bottle; one effect being his becoming increasingly violent. While Branwell continues his downward spiral, the sisters have been writing novels and sending them for publication. After her father has surgery, Charlotte begins work on Jane Eyre while aiding Patrick in his convalescence.

Branwell disappears for a lengthy period. Upon his return he is in terrible health; Branwell’s alcoholism is wreaking havoc on him. As the family tries to nurse him back to health, Charlotte receives a letter informing her Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey have been accepted for publication, but her novel The Professor has been rejected. Charlotte implores her sisters to go forward while she seeks a publisher for Jane Eyre.

The situation with Branwell worsens as tremendous success befalls upon the sisters. All three have novels published which all become wildly successful, but the family is forced to pay more of Branwell’s debts. Emily urges her sisters to reveal themselves and the huge success of their books to their father in order to alleviate his worries about their financial future. They agree on the condition Patrick does not reveal heir success to Branwell, fearing their accomplishing his dream will only worsen his condition.

However a bit of chicanery on the part of Anne and Emily’s publisher enrages Charlotte. After they attempt to pass off Anne’s work The Tenant of Wildfell Hall as Charlotte’s, she is adamant they go to London to reveal themselves as separate authors. While Anne agrees, Emily refuses in the interest of maintaining her anonymity.

Arriving at their publishers’ office, Charlotte introduces herself and Anne. Because of their enormous success, they are greeted with great enthusiasm. However, when the sisters return home, Emily tells them Branwell is gravely ill. Recovery eludes him and eventually, Branwell passes away.

The Hidden Sports Analogy:

They say hindsight is 20/20, but eyecharts only measure so much. Done correctly, looking back gives us glimpses at what was invisible in the present. Being woven into the fabric of it’s history, there’s no better example than baseball for America’s proclivity for self-distorted peaks at the past.

Don’t get we wrong, I’m not among those who find outrage under every rock and insist the only solution for past injustice is the immolation of the future. Perhaps I’m just an old black man pining for the days of honest racism; when it was a cultural flaw whose march against it was measured in societally-beneficial milestones rather it being manufactured as lubricant for the gears of self-serving American socio-political “repentance.”

There’s also a conundrum concerning whether life imitates art or vice versa. Being a bit of both, baseball also lends a lens toward past injustices, which is how it gives us a look at a the comparison between literature’s Brontë sisters and baseball’s Alou brothers. Be it “sex” or “race,” the root word is irrelevant. Both sets of siblings were overlooked due a myopic “-ism.”

We just explored the dismissive influence of sexism on the Brontë sisters. Despite the difference in arena and time, the Alou brothers have been overlooked for their role in eliminating their plaguing “-ism” from baseball.

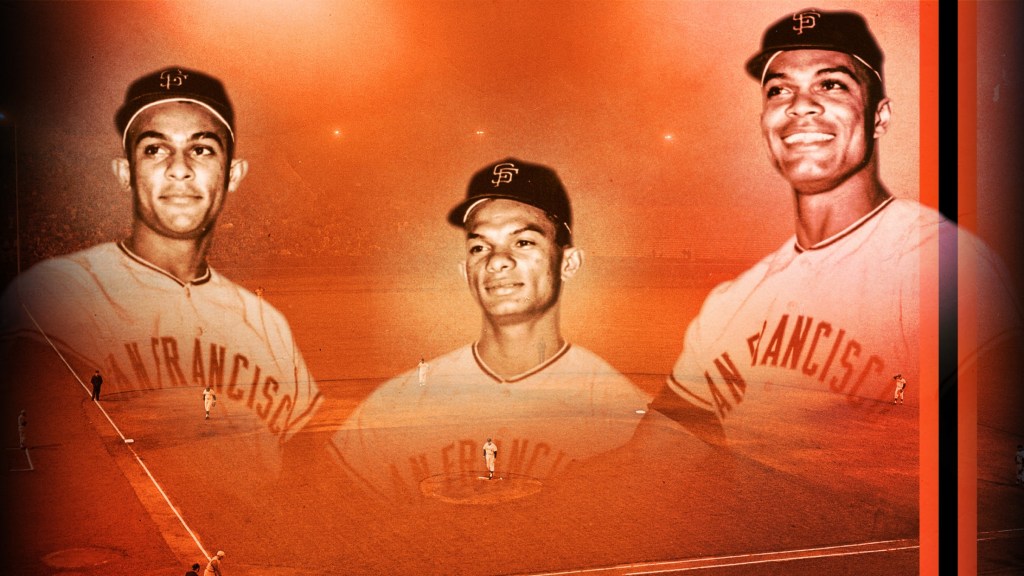

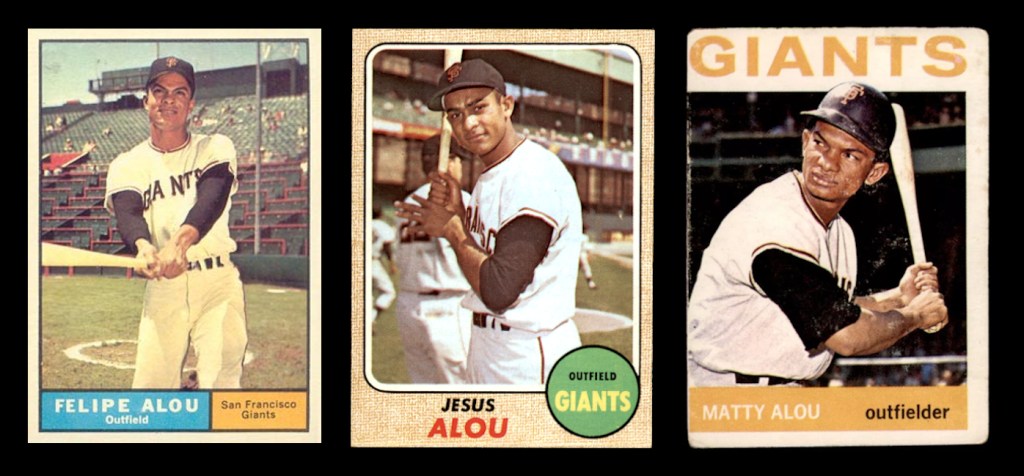

Felipe (b.1935), Matty (b. 1938), and Jesús (b. 1942) Alou were raised the sons of a Black carpenter/blacksmith and a Spanish mother in the Dominican Republic town of Haina. While he wasn’t the first Dominican to appear in a Major League game, Felipe Alou was the initial “every day” from the island nation. In a 17-year career, Felipe Alou played for the San Francisco Giants, Atlanta Braves, Oakland Athletics, and New York Yankees between 1958 and 1974. With a career that long featuring three All-Star Game appearances, while he isn’t going to the Hall of Fame, he was a damn good player.

The trail into big-league baseball blazed by Felipe soon would be followed by his younger brothers. Matty Alou played from 1960 to 1974 for the San Francisco Giants, Pittsburgh Pirates, St. Louis Cardinals, Oakland Athletics, and New York Yankees. Jesús Alou’s career was roughly as long as both his brothers; between 1963 and 1979 his major league stops included the San Francisco Giants, Houston Astros, Oakland Athletics, and New York Mets.

Much like the accepted societal norms of the day worked against the Brontë sisters, baseball floated with the racial currents of 1950s America. Despite their talents, the Alou Brothers discovered both their sport and their adoptive country were still in the painful midst of growing out of segregation. In an interview with writer Jeff Blair of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Felipe Alou told an interesting tale.

“I knew a bit about the history of the slaves, but I thought it (racism) was just a baseball thing. I had white aunts and uncles. We still have family with green eyes and blond hair. I get relatives who come and visit me in Florida, and nobody thinks we’re related.”

~ Felipe Alou

Alou would come to know the nature of American racism in 1954 in Miami upon learning he was required by law to ride at the back of city buses. And while Rosa Parks made a symbol of racial progress from a bus, we have yet to transport ourselves as a nation to a place of intellectual honesty when it comes to American history. The fact the Alou Brothers are a mere footnote in baseball history exemplifies that.

The culture of baseball is one that simultaneously embraces its history while reflecting the norms of a nation that doesn’t. Not only is that anathema to intellectual honesty, but it is driven by a class whose need to white-wash the past causes them selectively to ignore parts of it.

But nobody ever talks about September 15th, 1963. On that date, Felipe, Matty, and Jesús Alou appeared together in the same game manning all three outfield positions for the San Francisco Giants. This made the Alous the first…and to this day…the only “all-brother” outfield in Major League history.

In all fairness, that moment is more about trivia than cultural impact; this was fifteen years after Jackie Robinson. But the same heavy-duty baseball historians who take communion on the stories about the father-and-son Griffeys and the select club of three-generation baseball families largely ignore the Alou brothers. Let’s be honest. If the DiMaggio brothers (did you even know Joe had two brothers who played in the big leagues?) ever played together, it would be on baseball’s calendar.

I’ve mentioned Jackie Robinson more than once in this piece, and for good reason. One would think that for as much as baseball bends over backwards in atonement for the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” the Alou brothers would receive more recognition. While Puerto Rican Roberto Clemente is mentioned in that link as part of the Pittsburgh Pirates fielding baseball’s first all-black team in 1971, it’s only because he’s a Hall of Famer. As mentioned, the Alou brothers were not.

But the thing Clemente, the Alous, and other players of African descent from Latin America have in common is they are the “wrong” kind of black. As racism ebbs and flows as a cause celébré in America, one constant is that slavery outside of what would become the United States is completely ignored.

It would be the height of difficulty to underestimate the power of “white guilt” in the American socio-political landscape. A crucial component of that self-condemnation is the clinging to a bizarre narrative that somehow slavery was inherently worse in a cotton-chopping English colony than a Spanish one with sunshine and sugar cane.

In fact, the entire self-flagellating nature of “white guilt” depends on the delusion that slavery was a uniquely American experience. The sting of the self-lash is lessened by the fact slavery existed across the length and breadth of the New World, regardless of whether the colonial masters were English or Spanish…or French, Portuguese, or Dutch. After all, Jackie Robinson’s ancestors were brought here on the same slave ships that brought Roberto Clemente’s, the Alou brothers’…and mine. I’d be willing to bet our forefathers didn’t care about the destination after being kidnapped, shackled, and sold.

So…why do we?

Welcome to the inconvenient truth in all of this. As the societal currents flowed through time from slavery, past the Brontë sisters, and up to the Alous, they made all wet the “-isms” which affected them. The thread binding the Brontë and the Alous is what we today call “identity politics.” But a “rose” by any other name in any other time is still an “-ism,” meaning what you are matters more than who you are, and the value of “what” is completely arbitrary.

The bottom line is it doesn’t matter if you were a woman writer in the 19th century or a Dominican baseballer a hundred years later. Then as now, we are all still floating on those currents of “-isms.” The problem is we will always be on a self-sinking raft as long as we choose listening to those who ignore the progress from the past in order to flame the future.

The Moral of the Story:

They say blood is thicker than water. It’s certainly thicker than any “-ism.” Apparently, that applies to ink and pine tar as well.

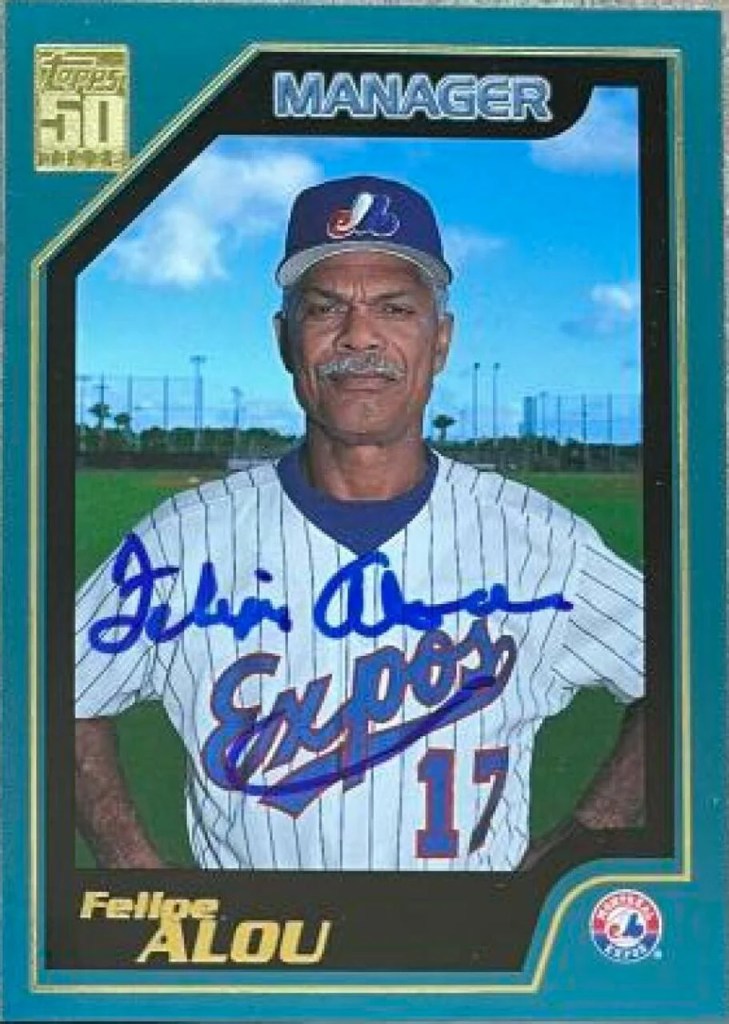

P.S. Felipe Alou also became Major League Baseball’s first Dominican manager when he took the helm of the Montreal Expos in 1992, winning the Manager of the Year Award in 1994.

He also managed those very same San Francisco Giants from 2003-2006.

P.P.S. For devotées of baseball history, Felipe’s son Moisés played a central role in arguably the most controversial moment for the Chicago Cubs…the Steve Bartman incident.

Got a question, comment, or just want to yell at us? Hit us up at dubsism@yahoo.com, @Dubsism on Twitter, or on our Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, or Facebook pages, and be sure to bookmark Dubsism.com so you don’t miss anything from the most interesting independent sports blog on the web.

[…] last installment in this series was all about a set of baseball brothers. While blood may be thicker than water, it isn’t […]

LikeLike