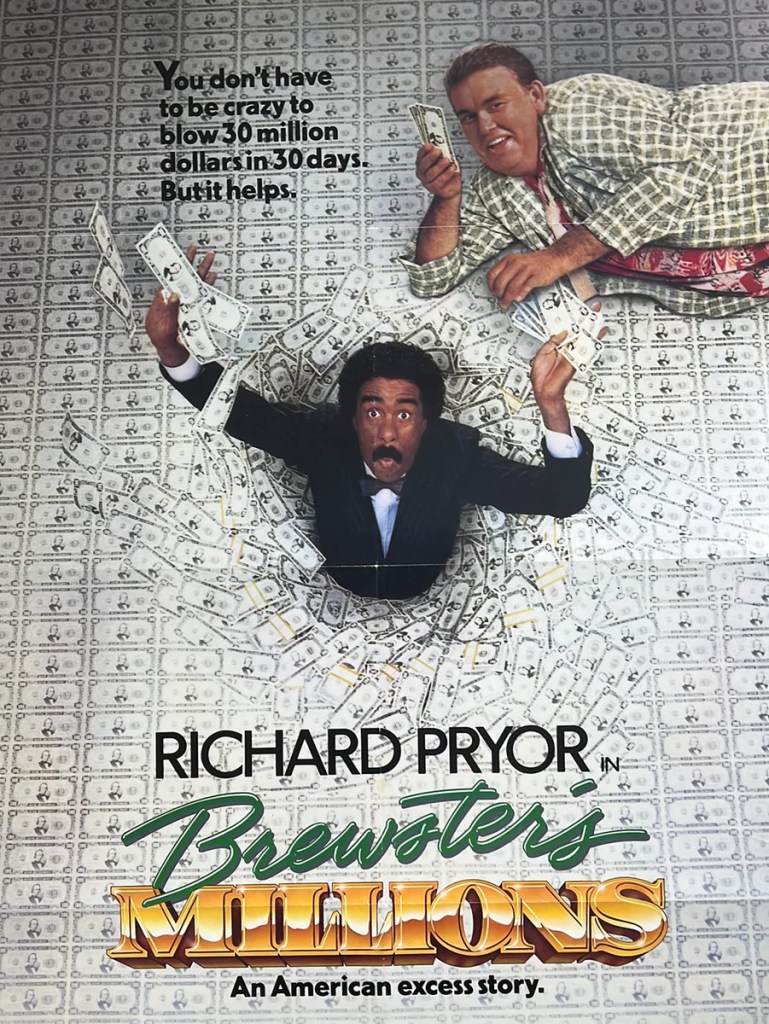

- Today’s Movie: Brewster’s Millions

- Year of Release: 1985

- Stars: Richard Pryor, John Candy, Lonette McKee

- Director: Walter Hill

This movie is not on my list of essential films.

Today’s installment of Sports Analogies Hidden In Classic Movies is just one of many contributions to a cool event called the Back To 1985 Blog-A-Thon. Because co-hosts Hamlette’s Soliloquy and Midnite Drive-In hit a home run with this concept, you can see all the great pieces contributed:

BONUS: I’m also killing the proverbial “two birds with one stone” with this installment as I was tagged in another event known as the Pick My Movie Tag. Another of my favorite bloggers Taking Up Room nominated me for this event, and luckily this film fits the bill!

The Story:

Given the title of this event. this is not about the 1945 film of the same name…although they are both based on the eponymous 1902 novel by George Barr McCutcheon.

Montgomery “Monty” Brewster (played by Richard Pryor) is a career minor league pitcher for the Hackensack Bulls; a team so far down the hierarchy of organized baseball they have a railroad track running through their outfield.

One night, Monty and catcher Spike Nolan (played by John Candy) are in a bar trying to hook up with two women when they are confronted by two hulks claiming to be the women’s husbands. This quickly becomes a brawl with Monty and Spike ending up on the losing end, not to mention landing in jail. Because of this, Bulls’ manager Charley Pegler (played by Jerry Orbach) tells them they have been released.

Meanwhile, Monty and Spike’s day in court doesn’t go well as they draw a wholly unsympathetic judge. But just when things look the bleakest for our minor-league battery mates, a photographer named J.B. Donaldo (played Joe Grifasi) tells the judge that he represents an unidentified party that will post bail for both Monty and Spike if they plead guilty.

Monty gets it in his head that J.B. is a major-league baseball scout, especially when he takes Monty and Spike to New York City. But instead of something baseball related, they are taken to the Manhattan law office of Granville and Baxter. Monty then discovers his recently deceased great-uncle whom he has never met has left him his entire fortune. Monty’s great-uncle Rupert Horn (played by Hume Cronyn), leaves Monty in a position to becomes fabulously wealthy…but there’s a catch.

The last will and testament is on film showing the sickly and ill-tempered Rupert in all his splendor. In order to teach Monty to hate spending money, Rupert has arranged a challenge in which he will be given $30 million to spend in 30 days. That sounds easy enough until the conditions of the challenges are established.

1) Monty cannot reveal the will’s terms to anyone. He is only allowed to disclose he has inherited $30 million. The reason for this is Rupert doesn’t want anyone directly helping Monty spend the money. That means only the law firm’s senior partners George Granville (played David White) and Norris Baxter (played by Jerome Dempsey) along with Rupert’s lawyer and executor Edward Roundfield (played by Pat Hingle) know the full details of the challenge.

2) Monty may only spend the money in exchange for tangible goods and services. The catch here is that if anything Monty buys accrues value, such as an investment which increases in value or property that generates income, that gain will be considered part of original inheritance and must also be spent.

3) Monty can’t give or gamble the money away. Charitable donations, just handing money to people, and/or gambling losses were capped at 10%.

4) Monty is not allowed to damage or destroy anything he buys.

5) Monty must be completely broke at the end of the 30-day challenge.

If any one of these five rules are broken, Monty loses and inherits nothing, and the law firm gets the $300 million. If he doesn’t spend every penny of the $30 million, what’s left will go to the law firm. Considering Monty’s highest-ever annual salary was $11,000, he takes the challenge.

Monty’s first move is to hire Spike as the vice president of an investment corporation. At the bank which holds all the money, Monty hires one of the security guards as his personal security, and rents the bank’s vault while refusing to start an interest-earning account.

A Russian taxi driver (played by Yakov Smirnov) just happens to be waiting in front of the bank; Monty hires him as a personal driver. The first plot twist comes when Monty is introduced to Angela Drake (played by Lonette McKee), the accountant Granville and Baxter have assigned to him.

Being young and attractive, Monty is instantly smitten with Angela. As a result, Monty tries to get a date with her, but he is coldly rejected as Angela tells him she has a fiancé. His name is Warren Cox (played by Stephen Collins), and he just so happens to be a junior partner at the law firm.

Monty really gets the challenge rolling by renting a penthouse and a large amount of office space in the Plaza Hotel. The money really starts flowing as Monty is spending it on everything he can while staying inside the rules of the challenge. He spends his days in his luxurious office entertaining the masses who by hook or by crook want to get their hands on his money. Monty also tells Charley Pegler to fix up the Hackensack Bulls’ field so he can arrange a three-inning exhibition game against the New York Yankees.

As part of continuing his spending spree, Monty is inspired by Spike to invest in expensive items like rare stamps. Monty buys the world-famous “Inverted Jenny” stamp for $1,250,000. In the next plot twist, Granville and Baxter read the story about the stamp in the newspaper; they believe by purchasing a rare collectible item Monty has violated one of the rules of the challenge.

However, as they are flipping through their mail, Baxter finds a postcard with a photo of the Hackensack Bulls and a message from Monty. With much consternation, Baxter realizes Monty used the “Inverted Jenny” stamp to mail the postcard, which completely de-values it. Furious, both Granville and Baxter meet with Warren where they show him the will, then order him to cause a hidden $20,000 bookkeeping error that will only be discovered at the last minute. For such chicanery, Warren is promised a full partnership in the firm.

Meanwhile, Spike and many others around Monty are becoming worried about his frivolous spending and attempt to intervene. Not only does this fail, but Monty begins doing things that to them are even more inexplicable. When Spike tells Monty he invested in a venture which generated a $10 million profit, Monty explodes exclaiming he’s “right back where he started!”

When Monty sees a television commentary about New York’s upcoming mayoral election, the reporter says his station will not endorse either candidate, insinuating they may have Mafia connections. Seeing a perfect opportunity to blow some big money, Monty enters the race with a declaration he is “None of the Above.”

Monty’s campaign does exactly as needed; the amount of advertising, staffing, and televised ads and drains much of the $30 million in no time. Monty openly attacks and insults his opponents, who then sue him for libel. Again to Monty’s advantage, he settles out of court for $4 million.

When game day for the exhibition between the Hackensack Bulls vs. New York Yankees game arrives, despite some early success, the Bulls lose; Monty surrenders the game-losing grand slam. Roundfield approaches a defeated Monty in the locker room to tell him he is leading in the polls, but if he wins the election, the $60,000 annual salary given to him as mayor would be considered an asset in accordance with the will. As a result, Monty announces his withdrawal from the race, and invites everyone to a final party…paid for with his last $38,000.

The next morning marks the 30th and final day of the challenge, and Monty believes he has everything running according to schedule. The landlord for Monty’s offices and penthouse evict him and the tailors repossess all the clothes he rented. Monty dons his old Chicago Cubs jersey to leave the Plaza for the last time…disappearing completely penniless into Manhattan.

At 11:50 pm, Monty reappears at Granville & Baxter to finalize the will. But before he gets to the senior partners, he is intercepted by Warren who gives him the “accidental” $20,000. Monty now believes he’s lost the challenge and agrees to sign the paperwork. Just then, Angela appears to accuse Warren of cheating. Naturally, that gets her fired, but this allows Monty to hire her as his attorney for…you guessed it…$20,000.

As she writes him a receipt just before the clock struck midnight, Roundfeld declares Monty has met the challenge. At this point, also promises to investigate Granville and Baxter for any wrongdoing for revealing to Warren the terms of the will.

The Hidden Sports Analogy:

One of Monty Brewster’s great lines in this film is “If bullshit were money, I’d be a millionaire.” Because this movie has a baseball theme, it makes the perfect vehicle for pointing out an ugly reality about Major League Baseball. If you’re full of enough bullshit, you can be one of the worst owners in the game. Worse yet, in a Brewster-esque manner, there are owners in big league baseball being financial screwballs in order to get richer.

Like every other large enterprise, baseball is broken into two camps; the “haves” and the have nots.” Just as similarly in many such organizations, the “haves” pay the freight for the “have nots.” Call it “revenue sharing,” “wealth redistribution,” or any buzzword of your choosing, the bottom line is rich teams pay to support poor teams.

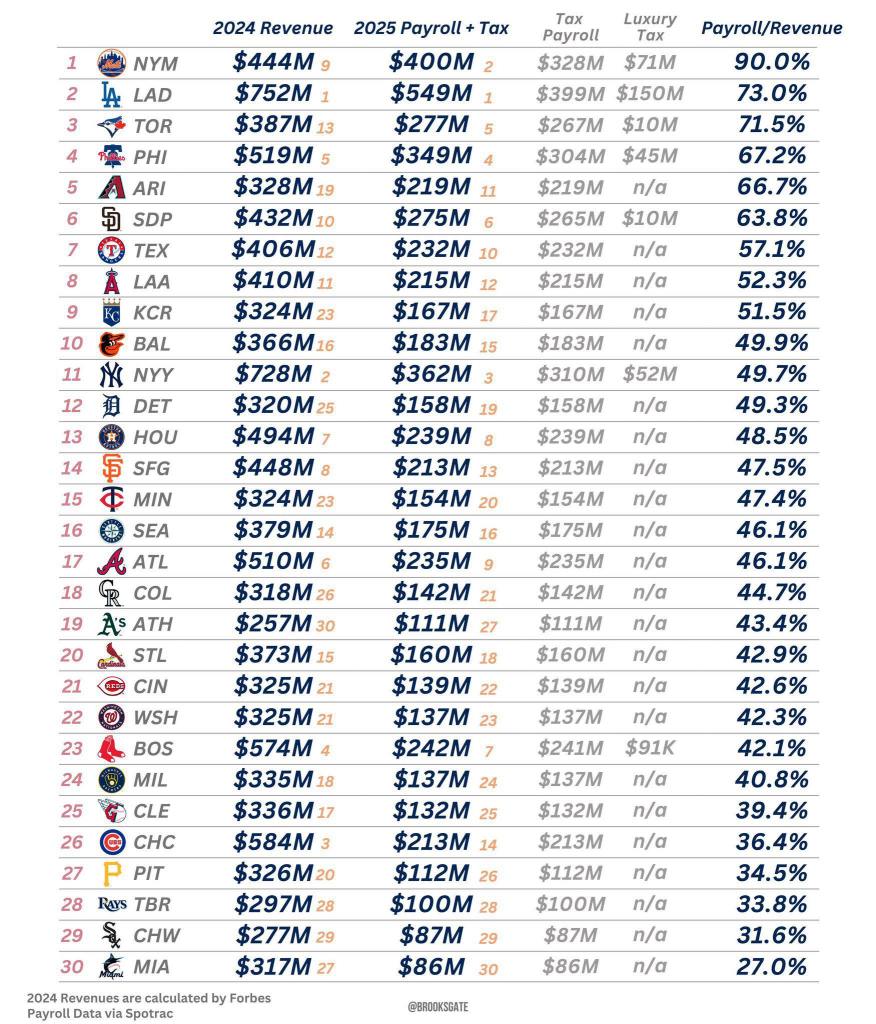

The “luxury tax” is baseball’s mechanism for doing just that. Formally known as the Competitive Balance Tax, it’s simply a financial penalty levied against teams whose payroll exceeds a predetermined threshold.

In 2024 (the last complete season for which the “luxury tax” was calculated), Major League Baseball set a new high-water mark in terms of the number of teams (9) who had to pay.

| Team | Total Taxable Payroll | Tax Assessed |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | $353,015,360 | $103,016,896 |

| New York Mets | $347,650,554 | $97,115,609 |

| New York Yankees | $316,192,828 | $62,512,111 |

| Philadelphia Phillies | $264,314,134 | $14,351,954 |

| Atlanta Braves | $276,144,038 | $14,026,496 |

| Texas Rangers | $268,445,491 | $10,807,106 |

| Houston Astros | $264,759,503 | $6,483,041 |

| San Francisco Giants | $249,108,939 | $2,421,788 |

| Chicago Cubs | $239,851,546 | $570,309 |

All tolled, that’s $311,305,310 MLB collected…a big chunk of which goes to goes into the Supplemental Commissioner’s Discretionary Fund. Dress it up anyway you want, it’s a glorified slush fund used by the Commissioner to augment the lowest-revenue teams.

Now, it’s time to take a look at the team’s who are getting paid. This can vary from year to year just like the number of payers will. But there’s a few “usual suspects” who have mastered the Brewsterian logic of the Competitive Balance Tax.

It’s no coincidence that all nine teams listed in the first table have all been in the play-offs at least once in the last three years; conversely there’s three teams in the bottom half of the table above that consistently remain profitable by keeping payroll on the cheap…and collecting a CBT check.

First, there’s the Colorado Rockies. Of our three examples, they have the highest payroll, and right now are currently on a pace to challenge the modern-era record for losses in a single season set by the Chicago White Sox. Either way, Colorado is a safe bet to lose at least 100 games for the third straight year.

Speaking of the Mighty Whiteys, they are coming off the aforementioned 121-loss season. Like Colorado, the White Sox also seem destined for their own third straight 100-loss campaign, but they may very well give the Rocks a run for their money headed for 122.

But the Pittsburgh Pirates are the poster-child for being deliberately and chronically non-competitive. The Bucs haven’t had a winning season since 2018 and Pittsburgh hasn’t seen October baseball since 2015. As of this writing, the Pirates are headed for 110 losses in 2025. If they achieve such an ignominious distinction, it will mark the fourth time in six years they have played at a 100-loss pace (less than a .383 winning percentage).

This is where the Monty Brewster analogy kicks in. Losing 100 games in a single season doesn’t just happen; so many things have to go wrong simultaneously. Doing it as often as the Pirates do can only mean one thing.

The Pittsburgh Pirates are more profitable as a loser than a winner.

Just like Monty Brewster, the Pirates engage in financial chicanery in the interest of a greater fortune. Throughout their history, the Pirates have been a “have not.” But thanks to things like the Competitive Balance Tax, all they have to do is spend their money in ways many don’t understand in order to ensure they still collect a check at the end of the season. That’s why there’s only a handful of teams who spend less of a percentage of their total revenue on player payroll.

That’s also why the Pirates haven’t won a World Series since 1979. In fact, Pittsburgh has only had two teams in recent history that have ascended to post-season play. In the early 1990’s, the Pirates captured three straight division titles with Barry Bonds, and a similar stint of success with Andrew McCutcheon in the early 2010s.

Both of those guys were MVP-caliber players who the Pirates let leave town. That cycle in Pittsburgh is about to repeat itself because as awful as the Pirates are now, they have a core of emerging stars like Oneil Cruz, Bryan Reynolds, and Paul Skenes. But the one thing we know for certain is Pirates’ owner Robert Nutting will continue the tradition; once it’s time for these young stars to get “star” money….they won’t get it in Pittsburgh.

Instead, Nutting has the “gets his cake and eats it too” version of Monty Brewster’s challenge. He wins by taking the “Wimp” clause in the sense that he throws his hand in the air, claims he can’t compete with the “big-market” teams, makes no effort to win or retain his best players…and at the end of the year collects a big, fat CBT check.

The Moral of the Story:

Legendary football coach Vince Lombardi once said “winning isn’t everything…it’s the only thing.” Of course, that was before everything had to be “fair.”

P.S. Jerry Orbach’s “Charley Pegler” is largely under-rated, but he made the Dubsism list of best movie baseball managers.

Got a question, comment, or just want to yell at us? Hit us up at dubsism@yahoo.com, @Dubsism on Twitter, or on our Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, or Facebook pages, and be sure to bookmark Dubsism.com so you don’t miss anything from the most interesting independent sports blog on the web.

Love this movie. Thx for playing.

LikeLike

I remember seeing this at the cinema, but had completely forgotten most of the cast. Thanks for the wee reminder!

LikeLike

Huh! I had no idea what this movie was actually about. But it sounds really good — one of those rare thought-provoking comedies! And Richard Pryor is always a good time. I will have to try to find and see it!

Thanks for joining the blogathon 😀

LikeLike

Thanks for explaining the luxury tax. I always figured it was some silliness to retain “competitive balance.” BTW, as someone born and raised in Hackensack, N.J. I can confirm that there were railroad tracks, but no baseball stadium.

LikeLike

Very interesting! I’m with Frank–the luxury tax was a mystery. This looks like a great movie, too.

LikeLike